This post is the start of a series discussing different grain hedging strategies that are utilized by grain producers and consumers.

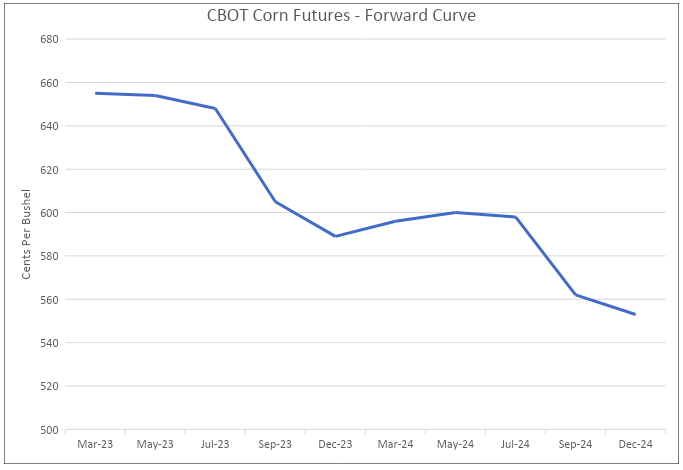

In the grain markets, there are a number of different grain futures contracts. Most of these contracts are traded on a few exchanges and almost all the futures exchanges are owned by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME Group).

Before we get started, let’s quickly review what a futures contract is. Buying a futures contract gives the buyer the obligation to receive the underlying commodity at a predetermined price, quantity, and location. Similarly, selling a futures contract gives the seller the obligation to deliver the underlying commodity at a predetermined price, quantity, and location. In practice, only a fraction of the futures contracts that are held go into the delivery process. Most are either bought or sold ahead of the delivery period.

So, how do grain producers and consumers use futures contracts to hedge their exposure to price changes? Let’s start by taking a look at the producer side.

Grain Hedging: Producers

Let’s assume that you are a grain farmer and would like to hedge your future corn production. It’s currently July, prices are good, and you think it’s a great time to lock in, or fix, some of your prices for the crop you are growing. Let’s assume that you are hedging corn that won’t be delivered to the market until March.

To hedge this requirement, you could simply sell a number of March corn futures contracts that corresponds to the amount of grain you would like to sell (each corn contract is 5,000 bushels). You would sell the March futures contract in this case, even though we are in July, because that is your anticipated delivery month.

To make things easy, let’s assume that you would like to hedge 5,000 bushels of corn (1 contract). If you had done so today, the price you would have received would have been $6.50/bu.

Now, let’s fast forward to February 28th, first notice day, or the last trading day of the contract before it goes into delivery. Because you do not want to make delivery of corn to the exchange, you buy back the contract that you had sold at the prevailing market price – offsetting your hedge.

For the sake of comparison, let’s look at two different outcomes. The first being that corn is trading at $7.25/bu at the end of February.

If corn futures were trading at $7.25/bu at the end of February, you would receive roughly $7.25/bu for the cash corn that you sold (excluding any basis, quality differential, etc). That 7.25/bu in cash grain would be offset buy a $0.75/bu loss on the futures contract that you sold, however, bringing your cash grain price back to your hedge price of $6.50/bu.

In the second scenario, let’s assume that corn futures were trading at $5.50/bu at the end of February. In this instance, you would sell your cash grain for $5.50/bu (excluding any basis, quality, etc), but you would have received a $1.00/bu gain on the futures contract. Once you add the $1.00/bu back to the cash grain price, the price you received for your grain is still $6.50/bu.

Grain Hedging: Grain Consumers

Grain consumers hedge their grain the same way that grain producers do – just using tools the opposite ways. In the example above, instead of selling a corn futures contract, a grain consumer would buy a contract.

In this instance, let’s assume you are a food manufacturing company that needs to buy corn as part of your normal business. It is currently January, you just set your budget for the year, and you have an estimate of what prices you need to achieve and what your volumes are.

After meeting with you risk committee and reviewing the risk policy, your team decides to hedge your July corn requirements. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume you need 5,000 bushels, or one contract, to be used in July.

In this instance, you would buy 1 July corn futures contract. If you would have done so today, you would have ownership of corn at $6.50/bu.

Now, let’s fast forward to June 30th, first notice day. Rather than hold a contract into the delivery period, you sell the contract back and agree to buy the physical corn through your supplier.

On June 30th, if corn futures were trading at $7.25/bu, you would purchase $7.25/bu through your supplier. You would also have a $0.75/bu gain on the futures contract that you hedged the grain with, however. The gain on the futures contract would offset the loss on the cash grain, bringing your pricing back to $6.50/bu.

Likewise, if on June 30th corn futures were trading at $5.50/bu, you would purchase corn through your supplier at $5.50/bu, but you would have a $1.00/bu loss on the futures contract. In this case, the gain on the cash corn price would be offset by the loss on the futures contract, bringing your pricing back to $6.50/bu.

While there are numerous other variables that come into play when grain hedging, the basic idea of a hedge is fairly simple. If you are a grain producer or consumer and you need, or want, to hedge your forward exposure to grain, you can do so by simply buying or selling a futures contract that corresponds to the date you plan to deliver or receive the grain.

As I mentioned at the top, this post is the first in a series on grain hedging. The following posts can be viewed here.

- Fundamentals of Grain Hedging – Options

- Fundamentals of Grain Hedging – Collars

- Fundamentals of Grain Hedging – 3-Ways

- Fundamentals of Grain Hedging – OTC Products.